Introduction

From past to present, content moderation has always being a key player in the media industry. Before the 21st century, individuals experienced an era of print and television media when content moderation is easy to implement. In the 21st century, such fantasy is no longer exist. The new media (social media) has changed the internet environment and content moderation framework. In discussing these changes, the blog will structure in three sections: First, what issues digital platforms face with content moderation. Second, debates in the implementation/enforcement stage of moderation. Finally, the discussion of the government/s role in regulating online content. Next, it is crucial to recognise some problems involving content moderation on social media.

Issues of moderation

Content moderation is an ongoing process in eliminating harmful communications which encounter social, political and economic dilemmas.

- Social

In the social aspect, the double standard and content moderators continue to affect the moderation effectiveness. In 2018, an investigation showed that social minorities often encounter harassment or abuse, but platforms have taken a negative attitude towards the issue for years (Jimenez, 2020). However, when Donald Trump encountered the same issue, the harmful contents was taken down immediately (Jimenez, 2020). It indicates the social bias of the platform in treating multicultural users and constitutes an unfair hierarchy in the online environment. Such hypocrisy is why content moderation is still problematic.

In addition, moderators are becoming a new form of digital labour paid to assist the platform in regulating content. However, moderators have been accused of bias in filtering content as they impose their values into the moderation process (Common, 2020, p. 132-133). The dominance of white males in the technological sphere reinforces the ‘White value’ in determining online appropriateness. Such ‘bro-culture’ phenomena indicate the ongoing gender inequality in the techno realm and society (Lusoli & Turner, 2021, p. 237). Furthermore, these moderators are facing enormous traumatise materials which constantly shaping their psychological state. Newton (2019) documented that Facebook moderators face low salaries, high layoff rates, abnormal working environments, and PTSD. They have been over-exploited by tech giants (e.g. Facebook) to become computer-liked machines which eventually leads their human rights and company’s governance into doubt.

Source: “Inside the traumatic life of a Facebook moderator ” by The Verge. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bDnjiNCtFk4

- Political

In the political aspect, globalization and diversification of the internet challenge platform in setting generous rules for a greater public. In America, platforms enjoy the ‘safe harbor’ policy, which exempts them from being responsible for harmful contents even they moderate (Gillespie, 2017, p.257-258). However, platforms are constantly receiving demands from different countries regarding content removal or deletion as it runs globally. These demands result in possible bans of platforms in certain countries (e.g. China, Middle East Nations) and reinforcing ‘Safe harbor’ policy reconsideration (Gillespie, 2017, p.259-260). These threats puts platform in the centre of political conflicts where a universal standard is needed. The foreshadowing of ‘Splinternet’ indicates user will experiences different contents and services according to different regions (Flew, Martin & Suzor, 2019, p. 46). Platform fragmentation has happened.

In addition, the large scale of user-generated content challenges the platform’s regulatory practices. The issue often arises from the platform’s mistaken deletion of positive contents and tolerance of illegal pornography. Users often found more severe content than the deleted one as Gillespie (2017, p. 270) argues that platform moderation has always been inconsistent. However, the inconsistency also provides flexibility to platforms as they can respond to the content according to its specific situations or value evaluation (Common, 2020, p.138-139). Therefore, inconsistency seems to be a great approach for the platform in combating different conditions but facing users’ demand for more transparency and certainty.

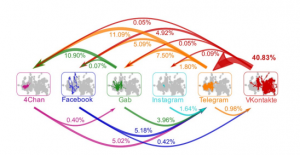

Moreover, the quick dissemination and revival of hate speeches have challenged every platform in the post-moderation stage. That is, what to do after the contents have been removed—especially in a decentralised online environment, where content creators are anonymous, clustered and hide in encrypted virtual networks ( Flew, Martin & Suzor, 2019, p. 42). In the current instance of the COVID-19 pandemic, hate speeches (incredibly racist speeches such as ‘Chinese virus’ or ‘WuHan virus’) has overwhelmed the online space.

The information is no longer individualised as Velásquez et al. (2021, p. 11549) argues platforms are not closed but intersected. Such interaction makes online extremists easy to escape and reinvigorated. They appropriate the transferability of platforms to spread COVID hate speeches and misinformation and generate links for harmful content to reach the wider public (Velásquez et al., 2021, p. 11549). Such diffusion put a question mark on the platform’s regulations and urged cross-platform cooperation.

- Economic

In the economic aspect, moderation can be problematic for platforms to generate revenue. As Gillespie (2018, p. 13) argued, moderation can be a commodity for a platform that can attract extensive traffics. The level of moderation has the potential to determine the flow of celebrities and relative fans. As a result, the platform struggles to balance profit and public interest, which may eventually adjust the business model.

Controversies of moderation

Since moderation is often challenging to implement, some controversies innovate the media industry to reconsider what counts appropriate. One significant example was the publication of “Napalm Girl” photograph filmed by Nick Ut, which triggered deletion from Facebook and public complaints towards traditional print media (Gillespie, 2018, p. 1-4). Both deletion and complaints have triggered a wide dispute about whether media should publish illegal images even if they embed deep meanings. The dispute has revealed the obscure moderation practice as Facebook Vice President Justin Osofsky (as cited in Gillespie, 2018, p. 3) argued that free expression and social protection is difficult to balance. Such two-sided effects also challenge societies (primarily culturally related ones) to consider the psychological impacts. These impacts raise the further issue of whether similar cases also have exceptions.

“Napalm Girl” by Terrazzo is licensed under CC BY 2.0

In addition, the freedom of speech has come into the debate with the ongoing platform moderation. Moderating individuals’ speech seems necessary in contemporary chaotic online environments, as Gillespie (2018, p.5) stated that a fully open platform is a fantasy. However, the level of moderation is challenging, as Donald Trump’s suspension on different platforms has amplified the issue (Hern, 2021). The suspension innovates two-side attitudes towards reconsidering the platform’s power and responsibility in restricting free speech. One side argued that instigate violence is inherently wrong, and the platform should overlook profit in such a situation (Hern, 2021). In contrast, the opposite side argued that it was a breach of free speech and addressed concerns about the power of Silicon Valley (Hern, 2021). Such debate has placed platforms in the centre of “public shock”, facing concerns and potential examination from the public (Flew, Martin & Suzor, 2019, p. 35). Thus, the scale of free speech has become a central question in the contemporary moderation process.

What role should government play?

At present, governments have always played the highest supervisor of online content in both the Eastern and Western worlds. It is the most potent force in shaping online practices and infrastructures. However, such force should have a scope; the government should not expand itself into deeper moderation. In the current state, many countries have taken necessary steps to restrict online content: America takes section 230 in “Communication Decency Act” (CDA)(known as ‘safe habor’ policy), China takes a paternalistic approach (high control and restriction), Germany takes “Network Enforcement Act” (NetzDG) to apply fine on unresponsible platforms and Korea takes “Network Act” to impose liability on platforms (Einwiller & Kim, 2020). Except for China, capitalistic countries all gives greater tolerance for platforms to respond and act. Such comparison indicates that the role of government differs in context, which means levels of moderation also differs culturally and politically. For countries like China, more moderation is not necessary as the government already taking a more significant role in content restriction. Whereas western countries, platforms should have rooms to control the regulations; Gillespie (2017, p. 262-263) argued that over-moderation seems aggressive and antiseptic for users. Thus, the government is still supervising the internet but with an appropriate scale.

Conclusion

Overall, content moderation is continuing to generate questions for platforms. The platform has received ongoing pressures from social, political and economic aspects. These pressures lead the platform to reconsider the practices of moderation and the implementation of regulations. Those controversies will continue to happen as long as social media is still an inseparable part of people’s life. It is crucial to recognise the moderation practices does perform differently based on different social and political contexts. Government’s should assign more power to platforms to ensure self-intervention is less needed.

![]()

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

References:

Common, M. F. (2020). Fear the Reaper: how content moderation rules are enforced on social media. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 34(2), 126-152. doi: 10.1080/13600869.2020.1733762

Einwiller, S. A. & Kim, S. (2020). How Online Content Providers Moderate User‐Generated Content to Prevent Harmful Online Communication: An Analysis of Policies and Their Implementation. Policy and internet, 12(2), 184-206. doi: https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/10.1002/poi3.239

Flew, T., Martin, F. & Suzor, N. (2019). Internet regulation as media policy: Rethinking the question of digital communication platform governance. Journal of digital media & policy, 10(1), 33-50. doi: 10.1386/jdmp.10.1.33_1

Gillespie, T. (2017). Regulation of and by Platforms. In J. Burgess, Alice E. Marwick & T. Poell (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social media (pp. 254-278). London, UK: SAGE Publications. See: https://ebookcentral-proquest com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/lib/usyd/reader.action?docID=5151795&ppg=277

Gillespie, T. (2018). All Platforms Moderate. In T. Gillespie (Eds.), Custodians of the Internet : Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions That Shape Social Media (pp. 1-23). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. See: https://www-degruyter-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/document/doi/10.12987/9780300235029/html

Hern, A. (2021, January 12). Opinion divided over Trump’s ban from social media. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jan/11/opinion-divided-over-trump-being-banned-from-social-media

Jimenez, K. (2020, October 8). Social Media’ s Double Standards for Trump. The Daily Campus. Retrieved from https://dailycampus.com/2020/10/08/social-medias-double-standards-for-trump/

Lusoli, A. & Turner, F. (2021). “It’ s an Ongoing Bromance”: Counterculture and Cyberculture in Silicon Valley—An Interview with Fred Turner. Journal of management inquiry, 30(2), 235-242. doi: 10.1177/1056492620941075

Newton, C. (2019). THE TRAUMA FLOOR: The secret lives of Facebook moderators in America. Retrieved from https://www.theverge.com/2019/2/25/18229714/cognizant-facebook-content-moderator-interviews-trauma-working-conditions-arizona

Velásquez, N. et al. (2021). Online hate network spreads malicious COVID‑19 content outside the control of individual social media platforms. Scientific reports, 11(1), 11549-11549. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-89467-y