As the Internet was created, the inequalities ubiquitous in our society were inevitably embedded into the features that make it up. It is interesting to explore whether the web has been a force for reducing or increasing said inequalities, specifically those that relate to gender discussions. Imbalance within Internet practices is known as the ‘digital divide’ and can have harsh real-world implications (DiMaggio et al., 2001). This manifests itself in a number of ways including disparities in the representation of men and women in online media, a more severe divide in developing countries and algorithmic sexism. However, the Internet has aided in positive developments in the plight for gender equality, such as feminist activism online. Nonetheless, gender inequality is undoubtedly ripe within our society and there are numerous aspects of the Internet that are merely exacerbating the climate we see around us. There are many more changes to be made to certain features of the web if the inequality is to be combatted.

Female representation in online media

The reality of the representation of women in online media is severe underrepresentation, both of those featured and journalists, as well stereotypical appearances and mentions. A study by Mateos de Cabo et al. (2014) analysed the representation of women in Spanish online newspapers to find evidence of underrepresentation, stereotyping and discrimination in online news. They discovered that females represented only 18% of individuals featured in news articles in the main Spanish online newspapers, concluding that stereotyping and marginalisation of women was underlying this vastly limited percentage. Ross & Carter (2011) point to the fact that online newspapers continue to box women into stereotypical ‘female’ sections, limited to a less newsworthy status all whilst being discriminated against by male reporters. This lead Megan Kamerick to argue that women should represent women in the media by telling their stories fairly and accurately.

Analysis of how often women are mentioned in the news compared to men (Photo by Sen Jia/Think Big)

Research has indicated that discriminative representation is very evident in online advertising by introducing distorted body image ideals (Plakoyiannaki et al., 2008). Advertisements of this nature can depict women in a derogatory and stereotypical manner, portraying women in an inferior way in relation to their competence and prospects. This is largely manifested in advertising by the depiction of women in traditional and cliched roles (Lysonski, 1985). On the whole, there was, and still is, unfair and discriminatory representation of women in traditional news and advertising, the avenues’ ever-growing presence online has merely allowed this discrimination to develop and expand.

The gender digital divide in developing countries

The severe digital divide in developing countries, where we see the intersection of gender and socio-economic background, is heightening the disparities in access to the Internet and, in turn, access to opportunities. The digital divide can be described, in its simplest form, as the gap between those who have access to Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and those who do not (DiMaggio et al., 2004). Antonio & Tuffley (2014) found that women in the developing world have significantly lower rates of access to the Interent than men do. They argued that this is a result of entrenched ideals regarding women’s socio-economic role in society. The concern is that the new technology in recent years has been exacerbating the inequality rather than ameliorating it (Antonio & Tuffley, 2014). These women then become further restrained to traditional family roles because they lack the basic digital literacy that would give them skills to obtain better opportunities (Telecentre Women: Digital Literacy Campaign, 2012).

“Coffee Pickers in Timor-Leste” by United Nations Photo is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

There is a clear need to strengthen girls’ and women’s capabilities on the internet in these societies, increasing their communication and knowledge by making ICT tools more accessible and affordable. If policy intervention was to address the socio-economic and cultural barriers these women face, improved support programs could be initiated with the potential to make a real difference. An example of a positive advancement is the #eskills4girls initiative that aims to bridge the gender digital divide in developing countries by increasing access to the digital world for girls and women, highlighted through a powerful illustration.

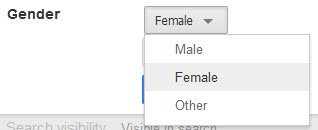

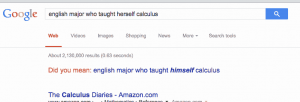

Algorithmic sexism

Yet another aspect of the internet that has societal inequalities embedded into is the supposedly neutral algorithms that are omnipresent on the web, ultimately demonstrating racial and gender exclusionary tendencies. Algorithmic systems that are constructed to make automated decisions are created by human beings, with their own set of values and ideals, many of which can be seen to promote racism and sexism. Race and gender representation in online media and search engines evidently have a dated history rooted in white supremacy and misogyny (Valdivia, 2018). Noble (2018) also pointed to the fact that a number of Google employees, involved in algorithmic decisions, circulated misogynistic memos, casting doubt of their gender neutrality. With evidence of such reckless and lack of regard for women and people of colour, it will become increasingly difficult for companies to argue the separation of their discriminative employment practices and their computer systems.

“Algorithmic sexism” (Photo by Alberto Cairo/Twitter image)

Noble’s writings do a distinguished job of providing a black feminist perspective and illuminating the, very evident, racial and gender biases of so-called neutral search engines. It should be said the usage of such scientific terms, such as ‘algorithm’ itself, masks the obvious subjectivity that goes into the creation of the systems and the continuation of oppressive structures in the process (Valdivia, 2018). This component of the internet has seemingly been subtly moulded by social inequalities and only serves to heighten the real-world implications of these disparities.

Social activism online

Despite the aforementioned ways components of the Internet have been forces for worsening the unjust imbalances in our society, there are aspects that contribute to redressing gender inequality, namely, online activism such as the #MeToo movement. In 2006, the movement was created by social activist Tarana Burke with aim of supporting victims of sexual violence (Shugerman, 2017). This resulted in thousands of women, all over the globe, sharing their stories, using the hashtag #MeToo on social media platforms. The movement managed to succeed in raising awareness of the pervasive issue and even hold some perpetrators accountable (Zhang et al. 2020).

“Can You Hear Me Now? #MeToo” by alecperkins is licensed under CC BY 2.0

A content analysis of Twitter at the time of peak traction credited the use of hashtags with managing to mobilise the movement by allowing users to connect the issue online so seamlessly (Xiong, Cho & Boatwright, 2019). The goal of hashtag activism is to use the symbol to create conversations about social issues between disparate Twitter users with a combined aim of combatting social injustice (Berridge and Portwood-Stacer, 2015). The case study of the #MeToo movement demonstrates the promise of digital feminist activism as a force for creating community, connection and support for women in solidarity (Mendes, Ringrose & Keller, 2018). This, ultimately, illustrates the way in which the Internet can be used as a tool for extremely positive movements towards combatting gender inequality.

So, why does this matter?

Evidently, the Internet we see today has embedded with it a plethora of structural inequalities that serve to intensify discriminatory practices against marginalised groups, including women. Looking at female representation in online media, the digital divide in developing countries and algorithmic sexism as areas of concern on the web, highlighted the potential for Interent practices to exacerbate real-world inequalities. Yet it would be unjust to ignore the ways the Interent has played a role in combatting gender issues such as in the fight against sexual violence by creating conversations and raising awareness. However, more policy intervention and inherent structural changes to the Interent are necessary if any progressive aspects in this respect are going to outweigh the harms done.

References:

Berridge, S., Portwood-Stacer, L. (2015). Introduction: Feminism, hashtags and violence against women and girls. Feminist Media Studies, 15(2), 341–344. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2015.1008743.

DiMaggio, P., Hargittai, E., Neuman, W. R., & Robinson, J. P. (2001). Social implications of the Internet. Annual review of sociology, 27(1), 307-336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.307

DiMaggio, P., Hargittai, E., Celeste, C., & Shafer, S. (2004). Digital inequality: From unequal access to differentiated use. In K.M. Neckerman (Ed.) Social Inequality (pp. 355–400). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Lysonski, S. (1985). Role Portrayals in British Magazine Advertisements. European Journal of Marketing 19(7), 37–55. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000004724

Mateos de Cabo, R., Gimeno, R., & Martínez, M. (2014). Perpetuating Gender Inequality via the Internet? An Analysis of Women’s Presence in Spanish Online Newspapers. Sex Roles, 70(1), 57–71.

Mendes, K., Ringrose, J., & Keller, J. (2018). #MeToo and the promise and pitfalls of challenging rape culture through digital feminist activism. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 25(2), 236–246. doi: 10.1177/1350506818765318

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Plakoyiannaki, E., Mathioudaki, K., Dimitratos, P., & Zotos, Y. (2008). Images of women in online advertisements of global products: does sexism exist?. Journal of business ethics, 83(1), 101-112. doi: 10.1007/s10551-007-9651-6

Ross, K., & Carter, C. (2011). Women and news: A long and winding road. Media, Culture & Society, 33, 1148–1165. doi: 10.1177/0163443711418272.

Shugerman, E. (2017). Me Too: Why are women sharing stories of sexual assault and how did it start?. Retrieved October 9, 2021, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/me-too-facebook-hashtag-why-when-meaning-sexual-harassment-rape-stories-explained-a8005936.html

Telecentre Women: Digital Literacy Campaign. (2012). Retrieved October 9, 2021, from https://www.itu.int/net4/ITU-D/CDS/circulars-dm/DM/DM_2011/pdf/DM-064_SIS_POL_TWC_Letter_Campaign_Brief_en.pdf

Valdivia, A. N. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism by Safiya Umoja noble (review). Feminist Formations, 30(3), 217-220. doi: 10.1353/ff.2018.0050

Xiong, Y., Cho, M., & Boatwright, B. (2019). Hashtag activism and message frames among social movement organizations: Semantic network analysis and thematic analysis of Twitter during the# MeToo movement. Public relations review, 45(1), 10-23. doi: 10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.10.014.

Zhang, D., Pistorio, A. L., Payne, D., & Lifchez, S. D. (2020). Promoting Gender Equity in the# MeToo Era. The Journal of Hand Surgery. 45(12), 1167-1172 doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2020.07.004

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.