“How to tame the tech titans”, by David Parkins for The Economist.com, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Annie Sun. Group 9.

Introduction

What is ‘techlash’?

The Internet and Internet companies have created a better, more open world for us, and digital technology has always been seen as a valuable tool. This view shifted when The Economist presented ‘techlash’ in early 2018, referring to the public and government reaction to the growing dominance of large technology companies.

The public raised excessive concerns about platforms after a series of scandals involving market monopolies and violations of user privacy broke out on large platforms such as Facebook and Google. The extent to which existing media policies and regulatory regimes can address these concerns has raised questions.

The public concerns that lie behind the ‘techlash’

-

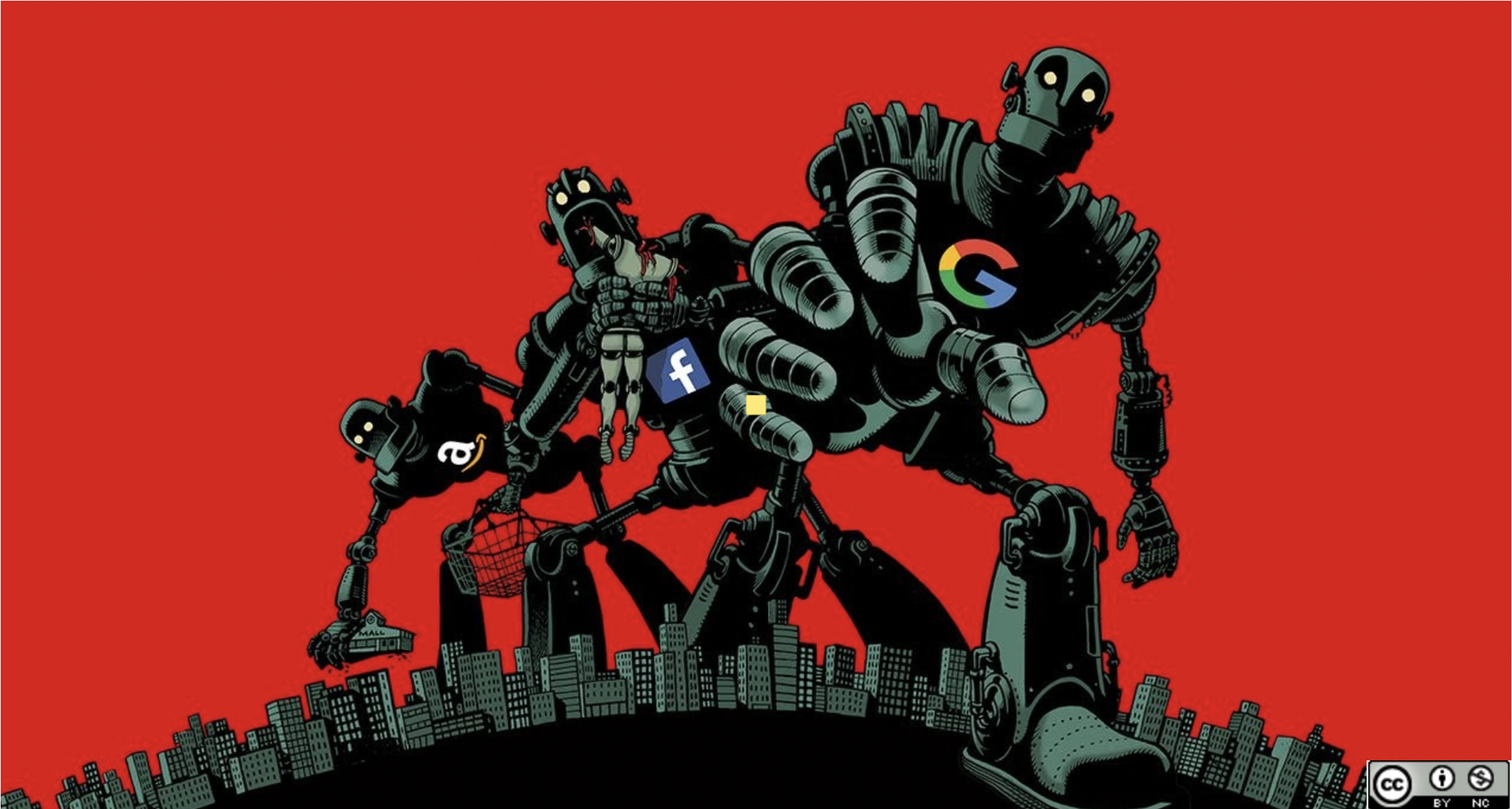

Monopoly and Unfair Competition

The growing power of digital technology has taken over almost all our communication, and the prevalence of the Internet and the use of social platforms in everyday life has made the Internet an oligopolistic market. According to data, Google handles 90% of web searches, Facebook controls 80% of mobile social traffic, and Amazon accounts for over 40% of the US online shopping market (Fiew et al., 2019). The Economist (2018) states, the dominance of these platforms is due to the “network effect”. That is, scale determines scale, and the more users a platform has, the higher its market position. In this situation, the big platforms rely on their dominant market positions to monopolise and suffocate their competitors. The public’s anxiety that big tech is monopolising the market has been heightened by the Facebook’s latest server outage. More than 3 billion users’ life and work were disrupted by the six-hour outage of Facebook and other apps that required Facebook permission

-

Invasion of user privacy

Data has been described as the new oil of the 21st century, and with multiple forms of Internet-based communication and socialisation, a massive trail of data from users is left on various platforms. The public is increasingly dissatisfied with the platforms’ practice of recording and analysing personal data during users’ daily lives and social interactions. This is especially true after Snowden’s revelations revealed close ties between large platforms like Microsoft, Google and Facebook and the intelligence community. In what has been described as the largest mass wiretapping and surveillance operation in human history, nine of the world’s largest Internet companies allowed the NSA direct access to their servers and collected Internet data from the public. This has led to public awareness that these platforms do not adequately protect the data entrusted to them by their users. Instead, Internet businesses profit handsomely from the sale of users’ personal data, and the use of user data by platforms becomes the core of their business model (Nikos, 2020).

-

Hate speech and Racial Discrimination

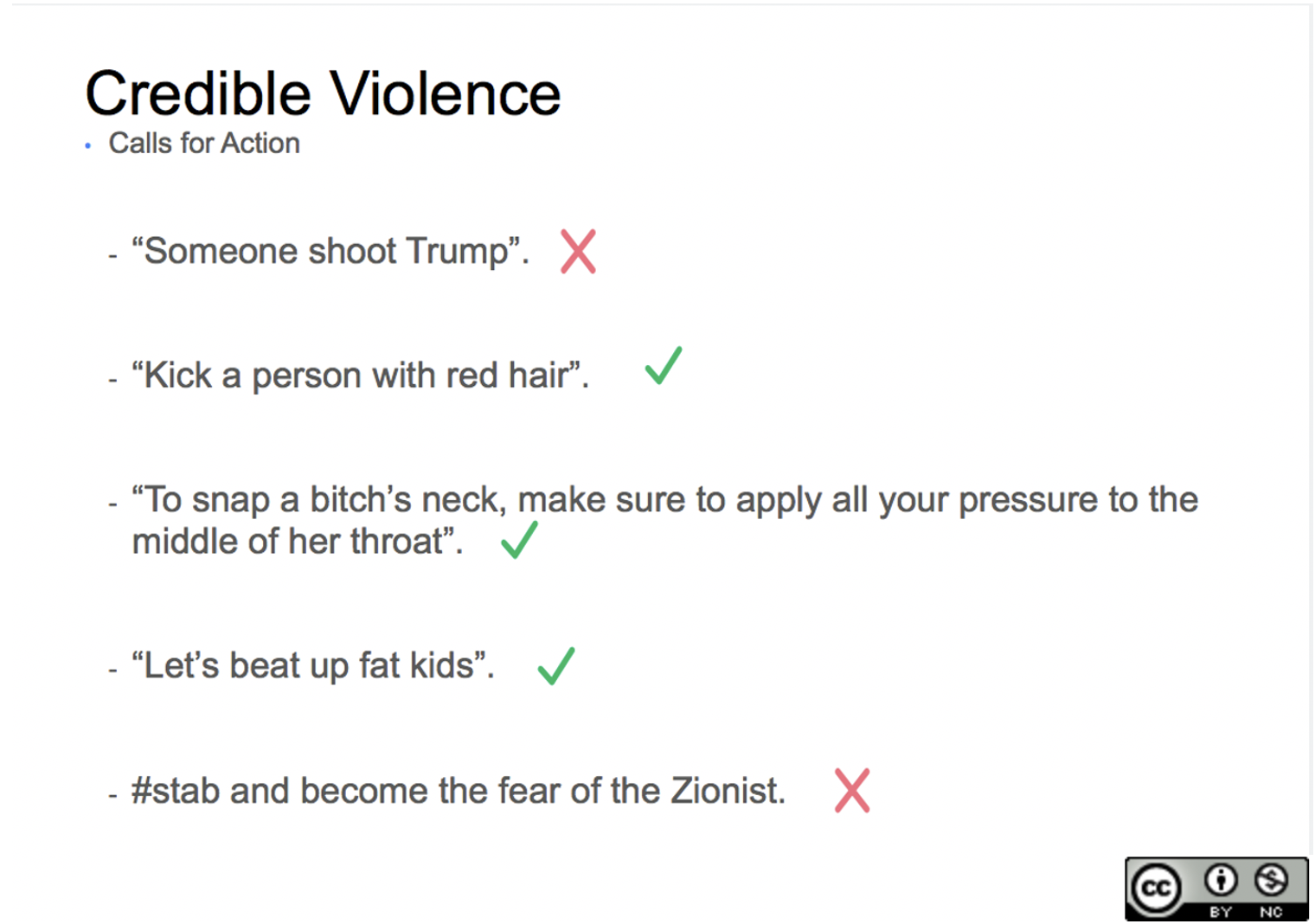

“Revealed: Facebook’s internal rulebook on sex, terrorism and violence”, by The Guardian, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The Internet was originally conceived as a platform for free speech, which means the right of free individuals to hold an opinion, even if that opinion is unpopular with the public. This idea is still powerful today, but it has raised public concerns about the harm that free speech can cause, such as online hate speech, extremism or promoting racism. While the platform has facilitated public communication and the dissemination of information, it has also brought harm. For example, in 2019, the shooting at the Christchurch Mosque was broadcast live on Facebook. Before that, Facebook deleted a video of police shooting Philando Castile, but then replied to the video and said the deletion was a “mistake”. These incidents demonstrate the extent of Facebook’s online hate and extremist content. Furthermore, threats of violence against women, children and various ethnic groups are not taken seriously, according to internal Facebook rules on how to handle inappropriate content revealed by The Guardian in 2019.

As these concerns intensify, governments and the wider public become aware of the rights and influence of global digital media companies, the need to regulate the online environment and content has become urgent (Fiew et al., 2019). Unlike traditional media, the large amount of real-time user-generated content and global reach makes regulation against digital platforms more complex and difficult. Therefore, governance for the Internet requires the involvement of multiple parties. Governments, civil society organisations and technology companies can all address the concerns raised by ‘techlash’ to varying degrees.

Regulatory Strategy

-

Self-regulation

For companies themselves, self-regulation is undoubtedly one of the most efficient methods, and this method usually falls under the category of “corporate responsibility” (Thomas, 2018). Compared with government regulation, self-regulation can be done quickly and effectively to set rules and enforce them. It can also further ensure the freedom of the platform. Under the influence of growing tensions, more and more social media platforms are taking on the responsibility of regulating their users’ activities. Although it is for the business purpose of maintaining corporate image and avoiding user churn, more targeted measures are still quite effective. For example, Facebook has established an independent oversight board, which is the Facebook oversight board (FOB), to ensure accountability and oversight of policies and teams. the FOB consists of 40 members and is used to review selected Facebook content and make rulings (Rotem, 2021).

On the other hand, the main motivation of platform companies is to profit by scaling up their businesses and expanding globally. A fair and impartial monitoring system contradicts the profit-making purpose of the companies, which means that there is a limit to how much self-monitoring the platforms can do.

-

Government regulation

Government regulation is relatively more enforceable, and a good system of external oversight plus some industry rules implemented through law make oversight more effective. For example, German hate speech law, which requires mandatory removal of speech that incites racial hatred, has been effective in curbing racial discrimination on platforms. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) introduced by the EU is seen as the foundation for global data protection and privacy standards. But there are still drawbacks to government surveillance (Fiew et al., 2019).

However, government regulation causes the rule-making and enforcement processes to take too long, and the government’s lack of understanding of digital technology has resulted in regulatory gaps. Additionally, the lack of uniformity in national legal systems combined with the multinational operations of most platform companies makes it difficult to enforce rules set by governments across borders. While the GDPR has been effective in protecting user rights, enforcement is limited to EU member states.

-

Civil society organisations regulation

The participation of civil society organisations in supervision can make citizens feel the necessity of regulation of technology companies in a personal way. This raises the public’s awareness of rights protection and effectively promotes public opinion in favor of regulation. Compared to the singularity of government regulation, civil society organisations can gather multiple forces as well as professionals for discussion. However, the efficiency of civil society regulation is limited, and final implementation still necessitates collaboration with the government and technology firms.

Conclusion

In regulating the Internet, no regulatory system is completely effective. Regulating in a competitive global arena means that no single nation or jurisdiction has the power to modify the Internet. To regulate and govern the Internet while guaranteeing its freedom, multi-party cooperation is the most effective method at this stage.

References:

- Flew, T., Martin, F., & Suzor, N. (2019). Internet regulation as media policy: Rethinking the question of digital communication platform governance. Journal of Digital Media & Policy, 10(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1386/jdmp.10.1.33_1.

- Smyrnaios, N. (2019). Google as an Information Monopoly. Contemporary French and Francophone Studies, 23(4), 442–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/17409292.2019.1718980.

- Nick, H. (2017). Revealed: Facebook’s internal rulebook on sex, terrorism and violence. The Guardian, 21.05.2017. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2017/may/21/revealed-facebook-internal-rulebook-sex-terrorism-violence.

- Hemphill, T. A. (2019). “Techlash”, responsible innovation, and the self-regulatory organization. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 6(2), 240–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/23299460.2019.1602817.

- Medzini, R. (2021). Enhanced self-regulation: The case of Facebook’s content governance. New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444821989352.