“de #metoo à #wetogether” by Jeanne Menjoulet is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

With the development and widespread use of Internet technology, it has become more convenient for people to obtain information, express themselves, and communicate across regions. The advent of the Web2.0 era has reduced the cost of Internet users expressing themselves, broke the tradition that audiences are in a passive position in mass communication, and promoted the Internet to become a gathering place for public opinion. However, the structural prejudices of the early Internet still affect the current digital culture. Turner (2021) points out that the contemporary Internet culture is still dominated by whites, men and the middle class. Since the 1990s, the critical impact of the digital gender gap on the female community has attracted attention. This impact is gender-imbalanced and is mainly manifested in the accessibility of information and communication equipment, gender discrimination in cyberspace, and digital identity security. On the other hand, the Internet also allows women to resist gender discrimination and gender-based violence.

Uneven share of digital resources

At present, the digital gender gap is a global problem, especially in developing countries. Women are 7% less likely to own a mobile phone than men, and 15% less likely to use the mobile Internet. In addition, the number of women accessing the mobile Internet is still 234 million fewer than men. (Carboni, 2021) According to ITU (2021), only about 25% of countries have achieved gender equality in Internet services. Although Internet technology promotes the development of gender equality to a certain extent, this approach also has limitations. The Internet has lowered the threshold for some women to participate in economic and social activities. Still, the digital gender gap has also led to excluding other women from the digital world.

“#CSW62 – Side Event – Closing the Digital Gender Divide – Making Universal Access and Service Funds Work to Connect Women and Girls” by UN Women Gallery is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Digital gender identity construction distortion

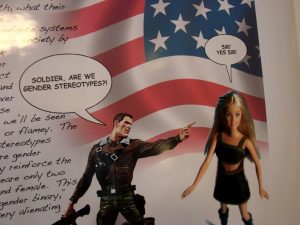

The shaping of gender roles in the digital space is rooted in whole society, and it also affects the construction of social gender. However, the proportion of women participating in the development and decision-making of Internet technology is much lower than that of men, making it difficult for women’s subjectivity to be reflected in the digital space. According to The Global Gender Gap Report 2018, only 12% of machine learning researchers are women, and women account for only 22% of global artificial intelligence professionals (World Economic Forum, 2018). Also, although women account for nearly half of the worldwide workforce, they only account for 31% of IT employees (Needle, 2021). Due to the lack of diversity in Internet research teams, algorithms written by humans for use in artificial intelligence have failed to get rid of gender discrimination (Bardon et al., 2020). For example, due to the absence of female workers in artificial intelligence, developers tend to project gender stereotypes on AI. AI that explores outer space, rescue humans, and engage in scientific research are designated as men, while AI involved in communications and services will be set as women.

“oberlin gender stereotypes” by istolethetv is licensed under CC BY 2.0

From the perspective of the Internet platform, since androcentric thoughts dominate the right to speak, it is easy to carry traditional gender discrimination concepts in Internet algorithms. Also, the majority of men at the decision-making level of technology companies is an important source of bias in the image of women. From the public’s perspective, the free discussion formed after receiving the information transmitted by the Internet has also continuously consolidated the prejudice of the female image.

Digital identity security is threatened

The security of digital identities in cyberspace is still highly vulnerable, especially for women. It means that women’s rights can easily be infringed by people who use Internet technology unethically. Moreover, this kind of infringement is spreading quickly and widely on the Internet. The anonymity of the digital space reduces the cost of such violence and the risk of punishment.

At the end of June 2019, DeepNude, a “one-click undressing” application, became popular online. With the help of neural network technology, this application only needs to upload a photo of a woman to automatically “take off” the clothes and forge realistic nude images. As of July 2020, the software has publicly released about 104,852 pornographic images on the TeleGram platform. In addition, 70% of these pictures are from real women in social networks, even minors. (Sensity Team, 2020) More importantly, this in-depth fake software is only for women. If you upload a male or any other inanimate photo, the system will automatically replace it with the female body and recognize it as the corresponding organ.

“deepfake” by ApolitikNow is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Sexual forgery is one of the many ways women are objectified in digital and visual culture (van der Nagel, 2020, as cited in Chandell & Jacquelyn, 2020). In the digital age, human faces and identity features are all digitized. The algorithm disassembles the identity of a person, and the identity traits in the traditional sense are decomposed and recombined with the identity traits of others to reconstruct. In other words, if algorithms are used, people will face a world that is more difficult to distinguish between true and false. When social panic intensifies and infringement cases occur frequently, women’s rights will face further violations.

The Internet: The Gospel of Anti-Gender Violence

As a medium of communication, the Internet breaks the limitations of time and space. Feminists and female rights defenders can use social media to spread ideas and help each other. It enhances the cohesion among people involved in the promotion of gender equality. Also, Internet activism paves the way for activists with mental or physical disabilities (or those who cannot participate in protests/rallies) to participate in meaningful discussions or actions (Mendes et al., 2018).

In Argentina, some feminists have created the hashtag #NiUnaMenos on Twitter to oppose the exemption for violence against women. Today, #NiUnaMenos has become a symbol of Argentina’s opposition to domestic violence. Chenou & Cepeda-Másmela (2019) argue that this online action not only broadens the channels for political participation by women who are not used to participating but also narrows the gap between experts and grassroots activists.

“#NiUnaMenos” by Jeanne Menjoulet is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

The Republic of Congo is currently piloting an app called Medicapt. This app allows users to collect, share and save forensic evidence after being sexually assaulted. It promotes cross-departmental communication and collaboration, strengthens the knowledge and awareness of proof required for legal cases, and improves the skills in recording, collecting and preserving forensic evidence of sexual violence (Naimer et al., 2017).

“PHR Year in Review” by physiciansforhumanrights is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The above cases can prove that the Internet has played an essential role in the promotion of gender equality in the world, especially in some countries with relatively weak awareness of gender equality.

Conclusion

From a global perspective, the prevalence of gender inequality is an indisputable fact, manifested in many fields such as politics, economy, and society. The existing gender norm is like a link in the social chain. When it meets Internet technology, the two will be linked together. With the gradual intercommunication, proximity and even close integration of the virtual society and the real-life society, as they become an extension of each other, Internet technology has also become another tool for constructing social gender in the subtle influence of social space. It means that gender inequality in real life will also permeate the Internet. Moreover, due to the digital gender gap and algorithmic gender discrimination, the Internet will magnify gender structural inequality.

At the same time, the Internet provides a free and open platform for feminists and female rights defenders. Therefore, more and more anti-gender violence activists are participating in online campaigns. In this regard, the Internet has brought new opportunities for achieving gender equality.

References

Lusoli, A., & Turner, F. (2021). “It’s an Ongoing Bromance”: Counterculture and Cyberculture in Silicon Valley—An Interview with Fred Turner. Journal of Management Inquiry, 30(2), 235–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492620941075

Carboni, I. (2021). The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2021 [Blog]. Retrieved 15 October 2021, from https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/blog/the-mobile-gender-gap-report-2021/.

Bridging the gender divide. ITU. (2021). Retrieved 15 October 2021, from https://www.itu.int/en/mediacentre/backgrounders/Pages/bridging-the-gender-divide.aspx.

World Economic Forum. (2018). The Global Gender Gap Report 2018 (p. 10). Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-global-gender-gap-report-2018

Needle, D. (2021). Women in tech statistics: The latest research and trends. WhatIs.com. Retrieved 15 October 2021, from https://whatis.techtarget.com/feature/Women-in-tech-statistics-The-latest-research-and-trends.

Bardon, A., Bernheim, A., & Vincent, F. (2020). “We must educate algorithms”. UNESCO. Retrieved 15 October 2021, from https://en.unesco.org/courier/2020-4/we-must-educate-algorithms.

Carboni, I. (2021). The Mobile Gender Gap Report 2021 [Blog]. Retrieved 15 October 2021, from https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/blog/the-mobile-gender-gap-report-2021/.

Sensity Team. (2020). Automating Image Abuse: deepfake bots on Telegram [Blog]. Retrieved 14 October 2021, from https://sensity.ai/blog/deepfake-detection/automating-image-abuse-deepfake-bots-on-telegram/.

Gosse, C., & Burkell, J. (2020). Politics and porn: how news media characterizes problems presented by deepfakes. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 37(5), 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2020.1832697

Mendes, K., Ringrose, J., & Keller, J. (2018). MeToo and the promise and pitfalls of challenging rape culture through digital feminist activism. The European Journal of Women’s Studies, 25(2), 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506818765318

Chenou, J.-M., & Cepeda-Másmela, C. (2019). NiUnaMenos: Data Activism From the Global South. Television & New Media, 20(4), 396–411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419828995

Naimer, K., Brown, W., & Mishori, R. (2017). MediCapt in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: The Design, Development, and Deployment of Mobile Technology to Document Forensic Evidence of Sexual Violence. Genocide Studies and Prevention, 11(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.11.1.1455