Image by sickboyy is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

The development of the Internet is changing the patterns of social interaction and reigniting debates about sexuality and identity, with the United Nations (n.d.) defining structural inequality as the unequal status accorded to one category of people in relation to others and the marginalisation of some groups. This article will focus on the theme of gender, using the modes of communication born from the Internet: memes and Internet buzzwords to illustrate how the masculinity and femininity transmitted by the Internet have reinforced gender stereotypes and gender inequalities.

MEMEs

The core of the Internet lies in openness and innovation, and one of its key features is the active participation of users in the production of content. People have developed and created a variety of forms to make online communication more interesting instead of content with simply surfing the web. The meme is a great example to illustrate, which people add creative or humorous phrases to a picture (sometimes a simple motion picture or short video) and send and distribute them to each other via digital platforms.

It is certainly a fun interaction, however, in some memes, the humour conveys the idea of gender inequality. These innovative ways of examples of online sexism and harassment are often redefined as ‘acceptable’, presenting them in new forms disguised as jokes and humour (Drakett et al., 2018, p. 109), and the number of internet users appear to be involved in reading and spreading and this humour online (Shifman & Lemish, 2010, p. 871).

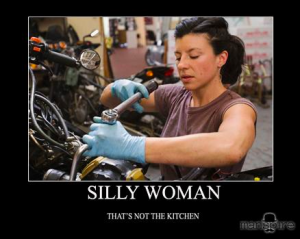

THE EXAMPLE OF A SEXIST MEME

tags woman get back in the kitchen by Jennifer Helms

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

The picture shows a woman is fixing a car, something that is usually considered more appropriate for men, the creator captioned it ‘SILLY WOMAN, THAT’S NOT THE KITCHEN’. Bing (as cited in Drakett et al., 2018, p. 111) argues that humour is not only entertaining, but also has a variety of potential functions, including maintaining and subverting hierarchies, creating solidarity within groups, or reinforcing boundaries and stereotypes.

As Shifman and Lemish (2010, p. 872) described, men are largely portrayed as rational, individualistic and independent in representation, and proved to be more culturally and technically oriented. Therefore, car repair work showed in the meme, is not something that people think women can do competently. Women are ‘SILLY’, they cannot take on this kind of work that requires skill, their place is just ‘KITCHEN‘, which confirms Shifman and Lemish’s (2010, p. 872) suggestion that women are considered with ‘being’/‘appearing’ in the private sphere. These meme works are trying to relocate women firmly in the domestic space (Drakett et al., 2018, p. 875), which not only conveys the idea that women are bad at skilled work but also ironically suggests that the outside world is not for women.

Women’s place is in the kitchen by Mary Glenn

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

While gender stereotypes can deepen impressions through these creative ways, leading to the marginalization of women in many areas of humour, the development of the internet has also given women the power to fight back. This meme is a rebellion to the memes on the last topic that the kitchen is where the knives are kept, but the ‘KNIVES’ are not just represent cooking utensils, but are dangerous, even murderous. It can also be considered as an instance that against these creators who put sexism and misogyny in the form of humour, is warning men who are influenced by gender stereotypes.

It cannot be denied that the internet offers a unique opportunity for marginalized social groups, at least in theory, to use it as an ideal medium to ‘liberate’ women’s humour, to express their unique voices in a serious and humorous way (Shifman & Lemish, 2010, p. 871), but sometimes with a serious threatening connotation. Although it can be seen as defiant, it certainly deepens the conflict between men and women and can also have the opposite effect, which amplifies some traditional representations of femininity that Shifman and Lemish (2010, p. 872) summarized: sensitive, emotional and vulnerable.

‘Internet Buzzwords’

Similarly, ‘Internet buzzwords’ is another creative way of communicating, but they have likewise become a vehicle for sexism. The development of the internet has facilitated cultural exchange between countries, also aesthetics are influenced and quietly changing. In China, for instance, the idol culture of Korea has become increasingly popular in recent years, especially after the popularity of Korean survival shows and Chinese entertainment companies starting to imitate, and some boys start to care about dressing, wearing make-up and jewellery. Teenagers have become attracted to the ‘Little Fresh Meat’ and have gradually started to admire these male celebrities who are labelled as white, thin, cute and sexy. As Song (2019, p. 11) introduced that this situation has led to concerns about unconventional gender expressions on the internet and in real life.

As a result, the term ‘Niangpao’ (娘炮, Sissy) was coined to describe feminine boys, or soft masculinity. The reason is that gender representation are ground in well-entrenched, historical constructions of femininity and masculinity as binary as well as hierarchical oppositions (Shifman & Lemish, 2010, p. 872).’ From this perspective, ‘Niangpao’ can be seen as a sign of male disdain and anxiety about femininity. Those boys who do not conform to the traditional image of masculinity, the ‘feminine beauty’ is sometimes described as a perverse aesthetic and perverted behaviour.

‘Niangpao’

“SO FUNNY! Han Peiquan says “They are CRAZY Candies”! 韩佩泉爆笑调侃学员开场白!“他那是糖果齁咸!” | 创造营 CHUANG2021″

Source: Youtube – https://youtu.be/etwfBePTh8E

This video is from CHUANG 2021, a men’s idol group survivor show. The boys in the video are in the middle of an introductory session, and their group name is ‘Sweet Candies’. They were trying to show their soft beauty and deliberately act cute, and the response they received from the competitor was: ‘I wonder if he’s too old to be giving a kindergarten show.’ The video caused a heated discussion at the time, “To act outside the idealised image of the heterosexual male is to be suspected. And to be suspected means to be labelled, stigmatised and ultimately punished” (Heasley, as cited in Zhang, 2019, p. 265), the criticism they received was basically that they were feminine and typically “unmanly”, people felt uncomfortable and unacceptable. The main reason for this is that their appearance and actions appear juvenile and contrary to conventional the idea of masculinity.

Keep Masculinity

“MEN’S EVERYDAY NATURAL MAKEUP TUTORIAL” Source: Youtube – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_ZycrzA_dxA

Moreover, women are often perceived to be more concerned with self-beautification and shopping (Shifman & Lemish, 2010, p. 885), for example, skincare and make-up are largely considered to be exclusively female items. As this mentions, pop culture and the beauty industry often suggest that cosmetics are designed to make women look attractive (White, 2019, p. 108). With the prevalence of iconic culture, men are also becoming conscious of their looks, but they use others to set themselves apart from women. A lot of male beauty bloggers emphasise ‘natural’ in their makeup videos. Harrison (as cited in White, 2019, p. 106) found that men’s makeup is “considered ‘corrective,’ that is, as addressing a health concern rather than a beauty issue,” to deny their involvement in the self-production of feminine forms of make-up, which only serves to promote the representation o masculinity.

It could be argued that normative masculinity limits gender embodiment. Research (White, 2019, p. 105) shows that men must “work on and discipline their bodies while disavowing any (inappropriate) interest in their own appearance“. Therefore, when boys are trying to be white, thin, cute and make-up will not be allowed. Due to the change in aesthetics, the military’s China National Defense Daily published an editorial that appealing that ‘young men foster true manhood and rid themselves of femininity by serving in the army’ (Song, 2021, p. 13) This is precisely the kind of denigration of women that seems to emphasise and indicate the hierarchy of inferiority of women over men.

Internet – Creative CHAINS

While the internet brings freedom, it also brings more accusations and regulations from strangers. It amplifies gender norms in an invisible way. These rules, which have limitations, are difficult for people to break out of their preconceptions. It may bring more negative comments to women, and prevent many men from truly expressing themselves, therefore deepening gender inequality.

Creative communications via Internet, Multiple ways of gender stereotypes by Tong Zhou is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

References

Drakett, J., Rickett, B., Day, K., & Milnes, K. (2018). Old jokes, new media – Online sexism and constructions of gender in Internet memes. Feminism & Psychology, 28(1), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353517727560

HRBDT. (n.d.) Ways to bridge the gender digital divide from a human rights perspective. http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/GenderDigital/HRBDT_submission.pdf

Pan, Z., Yan, W., Jing, G., & Zheng, J. (2011). Exploring structured inequality in Internet use behavior. Asian Journal of Communication, 21(2), 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2010.543555

Shifman, L., & Lemish, D. (2010). BETWEEN FEMINISM AND FUN(NY)MISM: Analysing Gender in Popular Internet Humour. Information, Communication & Society, 13(6), 870–891. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691180903490560

Song, G. (2021). “Little Fresh Meat”: The Politics of Sissiness and Sissyphobia in Contemporary China. Men and Masculinities, 1097184–. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X211014939

United Nations. (n.d.) ‘structural inequalities’. https://archive.unescwa.org/structural-inequalities#:~:text=Structural%20inequality%20is%20defined%20as,decisions%2C%20rights%2C%20and%20opportunities.

White, M. (2019). “You never want to ever looked caked in makeup”: Men’s Natural Look Makeup Video Tutorials. In Producing Masculinity (1st ed., pp. 103–134). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429054914-4

Zhang, X. (2019). Narrated oppressive mechanisms: Chinese audiences’ receptions of effeminate masculinity. Global Media and China, 4(2), 254–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059436419842667