Historicising the Internet is crucial to understanding how systemic race, gender, and class inequalities, faced by minorities, have been encoded into its design as it developed from a global computer network, in the 1970s, to the modern digital platform era. The initial optimistic visions of the New Communalists regarding a liberating Internet has been increasingly exposed as ignorant (Lusoli & Turner, 2021) since the privileges and freedoms of white, affluent males merely translated from society to the Internet, reinforcing this power imbalance at the expense of minorities (Noble, 2018).

Structural inequality: How has it shaped the Internet?

Structural inequality occurs when minorities are disadvantaged, typically for the benefit of historically dominant societal groups, embedding power imbalances and prejudicial biases in institutions such as government and the economy (Noble, 2018). These institutions, perceived as truth sources, normalise racial, gender and class hierarchies stemming from the colonial myth of white, upper-class male supremacy (Lusoli & Turner, 2021).

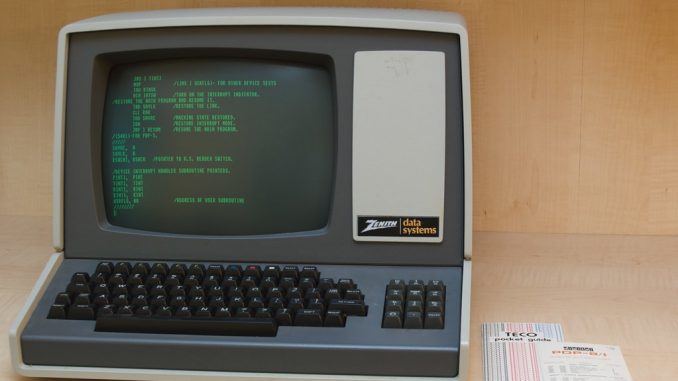

Despite the New Communalists’ cyberutopian hopes of the computer as a technology of freedom (Kelty, 2014), the Internet’s development has been greatly shaped by structural inequalities as the issue was, and remains, to whom this freedom is offered, and at whose expense?

As Lusoli & Turner (2021) reveal, the Internet’s creators and initial users were largely white, middle to upper-class American men in academic communities from which women, people of colour and the lower classes were often excluded. This cultural homogeneity meant that the views of this group have been encoded into the Internet’s design as minorities lacked the privilege of access and voice.

As Internet culture developed from the early techno-meritocratic scientific cultures, through to the virtual communitarians and the entrepreneurs of Silicon Valley (Castells, 2002), the unifying thread has been a highly problematic ‘bro-culture’ (Lusoli & Turner, 2021) which encodes gender, racial and class inequalities of capitalist hierarchies into the design and business model of the Internet, essentially colonising this ‘terra nullius’ with the same unequally distributed freedoms of society (Kelty, 2014).

Silicon Valley ‘Bro-Culture’ by Business Insider. Source: YouTube – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kRViy6pLmLM&t=1s

But the Internet isn’t entirely evil…

Indeed, the Internet’s sharing capabilities, tied to open-source movements (Castells, 2002) can help reduce structural inequalities through the decentralisation and mass dissemination of information in this networked information economy (Benkler, 2006). Freedom of speech (Kelty, 2014) and lower barriers to online participation also enables counterspeech to destabilise hate speech (Napoli, 2018).

In fact, according to the Pew Research Center (2020), from 2018-2020, the percentage of users who changed their views on social issues due to social media increased from 15% to 23%.

Online activism across the past decade has significantly facilitated this shift, with 52% crediting the #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) movement. BLM gained momentum following mass online circulation of George Floyd’s murder by police. In garnering widespread support, BLM has raised awareness of systemic racism through social media, encouraging legal action against the perpetrators of police brutality.

…it’s the actors behind the screen…

With even World Wide Web inventor, Tim Berners-Lee (2020), calling for structural changes to the Internet, these instances of social progress are the exception, not the rule, ultimately masking the harassment, misinformation and profit-driven oppression rife across Internet platforms.

…and the architectures they design

Welcome to the Internet by Bo Burnham. Source: YouTube – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k1BneeJTDcU

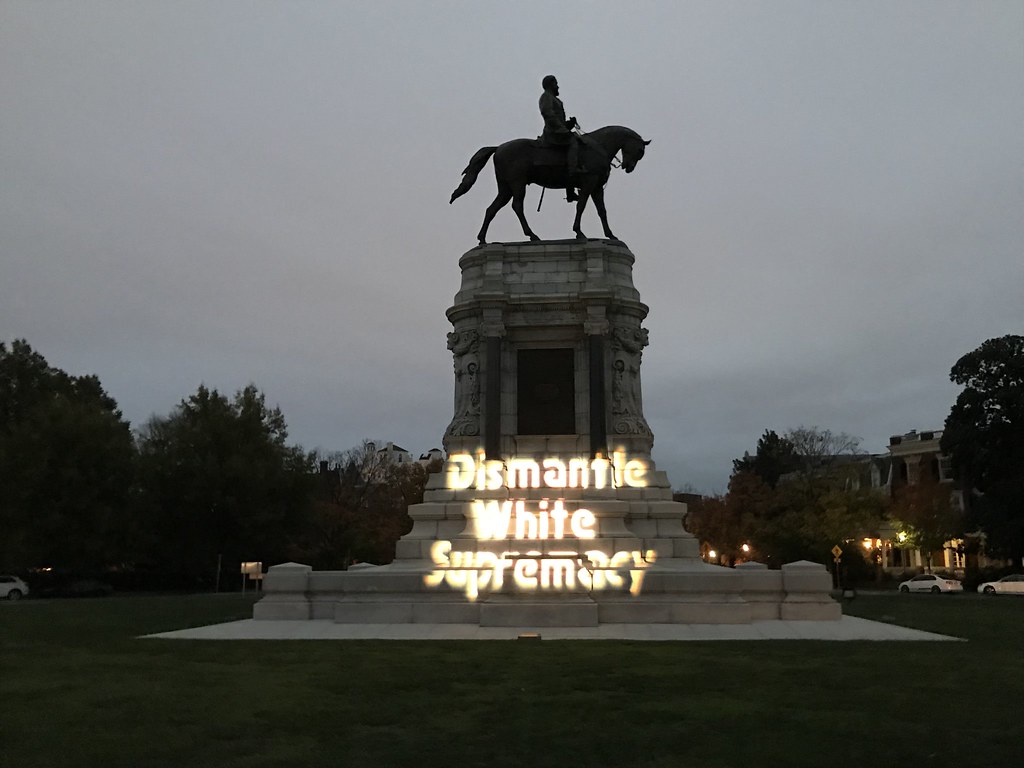

Behind the screen, profit-driven platform business models dominate the modern Internet (Mansell & Steinmueller, 2020), whereby search engines and social media platforms, namely Google and Facebook, collect and aggregate user data to psychographically profile them, selling targeted advertising spots with unprecedented accuracy (Flew, 2019).

As Noble (2018) reveals, the algorithms that drive content dissemination and prioritisation spread racial and gender biases encoded in and amplified by their artificial intelligence, primarily aiming to satisfy white males who supposedly possess the greatest purchasing power. This reinforces structural inequalities as the perceived neutrality of algorithms problematically conflates bias with fact, granting sexism and racism undue credibility. This is a product of Silicon Valley’s ‘bro-culture’ where a lack of diversity representation, particularly in leadership roles, means design reinforces societal patterns of advantage and disadvantage (Lusoli & Turner, 2021).

Filter bubbles: When tailored content becomes a trap

Users have become increasingly “less rational and more dogmatic” (Flew, 2019, p.95), trapped in ‘filter bubbles’ which reinforce their beliefs (Napoli, 2018) to maintain their commoditised attention (Pesce, 2017). Engagement metrics also cause them to associate positive engagement with truth, increasing vulnerability to misinformation through low-credibility content circulated by like-minded individuals (Mihai et al., 2020).

As such, algorithmic and confirmation bias problematise the democratic function of free speech online (Kelty, 2014) as the marketplace of ideas is increasingly fragmented and shaped by platform companies (Pesce, 2017), corrupted by neoliberal economic priorities (Popiel, 2018, p.580).

To function efficiently, algorithms also oversimplify identity, endowing data points, like gender and race, excessive value which promotes stereotyping that ultimately increases structural inequalities (Gerrard & Thornham, 2020). In fact, exposure to sexist stereotypes on Twitter has been shown to deteriorate perceptions of female job candidates, fuelling workplace discrimination (Fox et al., 2015).

Flexible labour and the sharing economy myth

The flexibility of labour, a legacy of the virtual communitarian’s misplaced idealism regarding Internet freedoms (Kelty, 2014), can be attributed to their disconnection from the working class, pushing these individuals to the bottom of capitalist social hierarchies, and to the edge in terms of safety and wellbeing (Lusoli & Turner, 2021). Today, multi-sided markets on platforms (Mansell & Steinmueller, 2020) promote precarity disguised as flexible labour (Roberts, 2019) as sharing cultures promoted in the open-source software movement (Castells, 2002) are colonised to economically advantage tech companies at the expense of disenfranchised workers (Nicholas, 2016).

In these exploitative labour arrangements, predominantly non-white, female and economically disadvantaged people, are engaged in precarious work which disproportionately exposes them to harm, thereby reinforcing structural inequalities. In this way, platforms such as Facebook routinely exploit minorities in a manner akin to the slavery practices of colonial history, for instance, through content moderation, whereby contract workers are regularly exposed to horrific and traumatising content with little psychological support or adequate remuneration (Gillespie, 2017).

“We see Facebook almost as a kind of new British East India Company, sending its tentacles out.” (Lusoli & Turner, 2021, p.241).

Similarly, the sharing economy, through platforms like Uber and Amazon Flex see these socially and economically marginalised individuals engaging in gig-work that endangers their safety and wellbeing, highlighting the sharing economy as a convenient facade for exploitation (Roberts, 2019). In a recent exposé, ABC News (McGrath, Smiley & Chalmers, 2021) reveals the fear and uncertainty Amazon Flex drivers experience regarding their terms of employment and pay with the delivery platform.

Food delivery drivers, contracted by platforms like Uber Eats, also face high risks of injury and death, with little insurance or renumeration (Begley, 2021), particularly evidenced during the COVID-19 lockdown in Sydney, Australia, where they lacked the workers’ rights held by other frontline workers, forcing them to work unprotected, health and policy-wise (Razik, 2021).

Sharing economy myths also mask exploitation of minorities’ intellectual property, manifesting on TikTok, where white influencers, such as Addison Rae, attain fame from the choreography of Black creators, often not crediting them.

Addison Rae Jimmy Eight TikTok Dances by The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. Source: YouTube – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VPgAfPlsSg0

Black influencer, Ziggy Tyler, has also exposed how TikTok’s content moderation algorithm prevents creators from identifying as ‘Black’, ultimately reinforcing structural inequalities that prevent non-white individuals from gaining economic advantage.

An update: (because apparently being black on that app isn’t allowed but being a neo nazi is? K. ) pic.twitter.com/9ecIf0tvPe

— Ziggi Tyler (@ZiggiTyler) July 6, 2021

Twitter Post by Ziggi Tyler. Source: Twitter – https://twitter.com/ZiggiTyler/status/1412549709592502273

Drawing the line

Taking into account the cycle of court hearings and ‘apology tours’ over the past decade, it is clear that platform companies use their significant lobbying and market power to avoid punishment by the government and legal system (Popiel, 2018), despite an onslaught of whistleblowers exposing their manipulative and exploitative activities. This raises the issue of whether structural inequalities will truly be addressed whilst they remain profitable, “subsum[ing] the public interests under corporate priorities” (p.566).

As the Internet continues to transform, this also raises concerns about the implications of algorithmic bias, labour precarity and inadequate regulation in future technologies like augmented reality whereby the ‘real’ and virtual world are increasingly enmeshed (Pesce, 2017). Will blockchain technology be the salve required, or will hierarchical inequalities find their way into the new technologies? Given the track record, the latter is more likely, even if to a lesser extent.

Hence, platforms cannot continue evading their social responsibility (Flew, 2019) as their editorial decisions (Gillespie, 2017) and corrupt business models (Mansell & Steinmueller, 2020) ultimately increase structural racial, gender and class inequalities for profit (Noble, 2018). However, regulation alone is not sufficient, because unless the underlying ‘bro-culture’ of Silicon Valley (Lusoli & Turner, 2021) is addressed, structural inequality will continue to be subconsciously and deliberately encoded into the Internet, and thus society, regardless of progressions in technology or law.

Colonising the Internet: A History of Encoded Inequalities by Olivia Di Costanzo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Reference List

ajmexico. (2009). Zenith Z-19 Terminal [Online image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/15587432@N02/3281139507

Begley, P. (2021, June 25). Food delivery driver’s death wasn’t recognised by Uber Eats and his family are still fighting for the insurance. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-06-25/background-briefing-uber-eats-delivery-drivers-death/100239920

Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: How social production transforms markets and freedom contract. Yale University Press.

Berners-Lee, T. (2020, March 12). 30 years on, what’s next #fortheweb. World Wide Web Foundation. https://webfoundation.org/2019/03/web-birthday-30/

Black Lives Matter [@blklivesmatter]. (2021, July 14). 8 years ago today, the words #BlackLivesMatter were penned and amplified by our beloved co-founders Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi. [Instagram Post]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CRRo-5DpEQr/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

boburnham. (2021, June 5). Welcome to the Internet – Bo Burnham (from “Inside” – ALBUM OUT NOW). [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k1BneeJTDcU

Business Insider. (2018, February 15). How Silicon Valley’s Sexist “Bro Culture” Affects Everyone. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kRViy6pLmLM

Castells, M. (2002). The Internet galaxy: Reflections on the Internet, business, and society. Oxford. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199255771.003.0003

Flew, T. (2019). Guarding the gatekeepers: Trust, truth and digital platforms. In A. Hay (Ed.), Griffith review 64: The new Disruptors (p. 94-103).

Fox, J., Cruz, C., & Lee, J. (2015). Perpetuating online sexism offline: Anonymity, interactivity, and the effects of sexist hashtags on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 436-442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.024

Gerrard, Y., & Thornham, H. (2020). Content moderation: Social media’s sexist assemblages. New Media & Society, 22(7), 1266-1286. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820912540

Gillespie, T. (2017). Governance by and through platforms. In J. Burgess, A. Marwick & T. Poell (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of social media (pp. 254-278). SAGE Publications.

Kelty, C. (2014). The fog of freedom. In T. Gillespie, P. J. Boczkowski & K. A. Foot (Eds.), Media technologies: Essays on communication, materiality, and society (pp. 196-220). The MIT Press.

Lusoli, A., & Turner, F. (2021). “It’s an ongoing bromance”: Counterculture and cyberculture in Silicon Valley—An interview with Fred Turner. Journal of Management Inquiry, 30(2), 235-242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492620941075

Mansell, R., & Steinmueller, W. E. (2020). Advanced introduction to platform economics. Edward Elgar Publishing.

McGrath, P., Smiley. M., & Chalmers, M. (2021, August 29). ‘No way to live’. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-08-29/amazon-flex-delivery-drivers-voice-safety-concerns/100404498?fbclid=IwAR0YxMI80tdC6CdnPKn-ur3moxivcPgRau1B8U9s_TiBBzD9AmQs8LMn7h8

Menczer, F. (2021, October 7). Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen testified that the company’s algorithms are dangerous – here’s how they can manipulate you. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/facebook-whistleblower-frances-haugen-testified-that-the-companys-algorithms-are-dangerous-heres-how-they-can-manipulate-you-169420

Mihai, A., Micallef, N., Patil, S., & Menczer, F. (2020). Exposure to social engagement metrics increases vulnerability to misinformation. The Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, 1(5), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.37016/mr-2020-033

Napoli, P. (2018). What if more speech is no longer the solution? First Amendment Theory meets fake news and the filter bubble. Federal Communications Law Journal, 70(1), 55-104.

Nicholas, J. (2016). The age of sharing. Polity Press.

Noble, S. U. (2018). Algorithms of oppression: How search engines reinforce racism. New York University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1pwt9w5

Perrin, A. (2020, October 15). 23% of users in U.S. say social media led them to change views on an issue; some cite Black Lives Matter. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/10/15/23-of-users-in-us-say-social-media-led-them-to-change-views-on-issue-some-cite-black-lives-matter/

Pesce, M. (2017). The last days of reality. Meanjin, 76(4), 66-81. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.284425064291885

Popiel, P. (2018). The tech lobby: Tracing the contours of new media elite lobbying power. Communication Culture & Critique, 11(4), 566-585. https://doi.org/10.1093/ccc/tcy027

Razik, N. (2021, July 7). ‘They have been ignored’: Calls to allow food delivery drivers access to COVID-19 vaccines. SBS News. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/they-have-been-ignored-calls-to-allow-food-delivery-drivers-access-to-covid-19-vaccines/2ca8ac15-4431-4634-a634-e8d1f506be00

Roberts, S. (2019). Behind the screen: Content moderation in the shadows of social media. Yale University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvhrcz0v

Statista. (2020). Workforce Diversity at Online Companies – Statistics & Facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/2540/workforce-diversity-at-online-companies/

Stock Catalog. (2018). facebook testify Zuckerberg [Online image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/151691693@N02/41347883051

Taggart, M. (2012). Thought Bubbles [Online image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/14681861@N00/8049224744

The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. (2021, March 27). Addison Rae Teaches Jimmy Eight TikTok Dances | The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VPgAfPlsSg0

Tufekci, Z. (2018, June 4). Why Zuckerberg’s 14-Year Apology Tour Hasn’t Fixed Facebook. WIRED. https://www.wired.com/story/why-zuckerberg-15-year-apology-tour-hasnt-fixed-facebook/

Ziggi Tyler [@ZiggiTyler]. (2021, July 7). An update: (because apparently being black on that app isn’t allowed but being a neo nazi is? K.). [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/ZiggiTyler/status/1412549709592502273?s=20