The regulation of content on Internet media platforms has become an increasingly exciting topic. The Internet has always been a fair platform, and its openness and freedom have attracted many users worldwide. However, there are two sides to everything, and the other side of openness and freedom is chaos and shadiness. So, what problems are revealed when the need for governance is realised? Moreover, the responsibility of regulating online content, should the government strengthen its regulatory policies? This is a series of questions that the whole Internet community needs to pay attention to.

“Fake News – Scrabble Tiles” by journolink2019 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Misinformation can lead to …?

Behind the open and accessible digital platform is chaos and darkness, which means there is a lot of fake news or hate speech. For example, the “Pizzagate” shooting in the run-up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election attracted much attention on Twitter. The incident began with tweets that then U.S. presidential candidate Hillary Clinton brutally abused children at a pizza parlour in Northwest Washington. Fortunately, there were no injuries, but the severity of the incident endangered the lives of the pizzeria’s owner and surrounding store operators. The second is the damage to candidate Hillary Clinton’s reputation, although a few days later, the incident ended with Donald Trump and his team stating that the information was fake.

“DID NOT ACT ALONE! INVEXTIGATE#PIZZAGATE!” byMarc Nozell is licensed with CC BY 2.0

Although the U.S. First Amendment expresses protection against some false statements to protect critical information, such as exaggerated descriptions of a candidate’s contributions and net worth, thereby enhancing his or her standing in the public eye. However, this incident runs entirely counter to that. Furthermore, it left much negative publicity. Gillespie (2018) suggests that the openness of the digital platform is not meant to be achieved. This is a double-edged sword, which, while achieving democratic openness, can also inspire much hostile rhetoric. In addition, Gillespie (2018) argues that people must be aware of the fundamental role of media platforms. As the role of digital platforms diversifies, people cannot ignore the ability of digital platforms to shape public discourse as well. Digital platforms have evolved from being a single intermediary of transmission to become the dominant ideological actors.

Awareness after regulation

As digital media platforms realize the need to act, more questions arise. The Internet is a global platform, with users coming from all over the world and living in different cultures, so consistency in the regulation of Internet digital platforms and the domination of the regulatory workforce is challenged. For example, Gillespie (2017) illustrates that Chinese social media platforms prohibit speech related to government territory. If it appears, it is removed and cooperation with the government so that the individual actions of users are restricted. This has led to large mainstream media outlets developing their policies to respond to foreign government requests. For Twitter, tweets will only be deleted if there is a policy for a particular region or country. This means whether the digital platform of the Internet will develop as one or whether it will split into digital media platforms. The consistency of content regulation on Internet platforms is challenged.

The second is the issue of content regulation technology and labour domination. Adopting appropriate regulation techniques and dominating the regulation workforce is another issue that needs attention. The existing approach to digital platforms is manual regulation and existing platform filter or removal policies. Roberts (2019) mentioned that in the post-industrial era, labour status and pay would be lower, and the quality of work will not be guaranteed due to the increased workload and time compression. Today, in terms of content regulation, the status of workers has not improved, and the cheapest workers are sought to compete in a globalised market. Digital platforms are not fully invested in content regulation and lack initiative.

Moreover, they are trying to create a platform for subjective judgment and political conservatism using a hard-liner approach of active deletion. However, in the case of the 2016 election “Pizzagate”, the effect of content deletion was small but still affected real-life citizens. Content regulation exposes broader social issues, such as differences between cultures, distorting and exaggerating them to assimilate more people’s minds. Then the manual supervision or supervision technology alone is far from enough, and the virtual community can see the essence through the phenomenon.

Content regulation has led to several effects, from an anonymous speech on platforms to the need for real-name verification. Most community users believe that real-name verification defeats the original purpose of free speech on the Internet and exposes users’ personal information. (Zhang & Kizilcec, 2014) Privacy exposure is not related to actual names or anonymity, as stealing information can be done under real names or anonymity and posting anonymously can lead to more hate speech or fake news. Furthermore, anonymous message board often contain radical content. (Zhang & Kizilcec, 2014) The debate over whether to publish anonymously or under a real name remains, as it is impossible to get the right policy on content regulation and only minimise the adverse effects.

“Chalking the Universal Declaration of Human Rights 2015” by University of Essex is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Whose responsibility is it to regulate content?

Most of the voices favour more robust government regulation of media platforms believe that there are laws or regulations in place to provide a level of deterrence to the purveyors of negative news. However, from another perspective, this would transfer more power to the government, and deterrence would not necessarily solve the problem entirely. For example, Singapore’s parliament passed “fake news” legislation that carries a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison or a fine of up to S$1 million (US$735,000). This has received criticism from human rights groups and Google and Facebook have argued that the law gives the government too much power. Frederick Rawski, director of the International Court of Justice for the Asia Pacific, said the law’s harsh penalties and lack of expressed protections would create more significant risks. Second, studies have shown that government intervention is limited only to violence-related content, as the impact of hate speech and false news is beyond the government’s jurisdiction. (Samples, 2019)

Furthermore, Gillespie (2017) argues that government and state interventions can affect innovation in the marketplace of ideas for virtual communities to some extent. This responsibility should not be attributed to the government or the platform itself but is a joint effort of both sides. The regulations issued by the local government are also limited to the local platform norms. The Internet is a global and highly interactive platform. In addition to the legal deterrent, the simplest but also important issue is to allow platform users to avoid publishing similar content by instinct. This brings us to the issue of media literacy, the ability to analyze true and false information in a virtual community critically. For example, Notley (2021) have shown that Australians are generally fewer media literate, often because they do not have the confidence in their media skills to judge false information on their own. Therefore, the government does not need to do additional intervention policies, the power will be evenly distributed to the platform and individual users, to enhance the media literacy of all people is perhaps the fundamental solution to the problem.

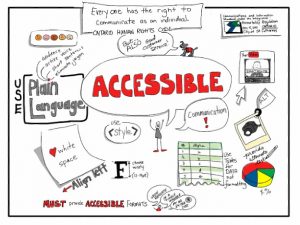

“Accessible Communication. It’s the Law!” by giulia.forsythe is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

When will the storm end?

Digital platforms realise it is time to adjust when the rhetoric of virtual communities has a negative impact and spills over into real life. In the adjustment process, the platforms are not very active in regulating content and the technology to regulate it. The regulation process has led to the discovery of a broader social problem where real-life injustices may be infinitely magnified and distorted and then spread to the Internet. Anonymity and real-name authentication are controversial in terms of privacy of personal information and freedom of expression; however, privacy is not compromised by anonymity or real-name authentication, but real-name authentication is indeed a way to deter and reduce the appearance of negative information. The content review includes standards of transparency and accountability, how content is defined and regulated, and how the workforce is employed, all of which require a more open approach. It will not be changed by additional government intervention but more by the rational use of resources by platforms and individuals’ proper handling of information. On the contrary, the storm of content regulation experienced by Internet media platforms will be much longer.

Reference

Gillespie, T. (2017). Regulation of and by Platforms. Ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=5151795.

Gillespie, T. (2018). All Platforms Moderate. Www-degruyter-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au. Retrieved from https://www-degruyter-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/document/doi/10.12987/9780300235029/html.

Napoli, P. (2018). What If More Speech Is No Longer the Solution? First Amendment Theory Meets Fake News and the Filter Bubble. Go-gale-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au. Retrieved from https://go-gale-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/ps/i.do?p=AONE&u=usyd&id=GALE%7CA539774158&v=2.1&it=r.

Notley, T., Dezuanni, M., Chambers, S., & Park, S. (2021). Less than half of Australian adults know how to identify misinformation online. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/less-than-half-of-australian-adults-know-how-to-identify-misinformation-online-156124.

Roberts, S. (2021). Behind the Screen: Content Moderation in the Shadows of Social Media.Www-degruyter-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au. Retrieved from https://www-degruyter-com.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/document/doi/10.12987/9780300245318/html.

Samples, J. (2019). Why the Government Should Not Regulate Content Moderation of Social Media. Cato.org. Retrieved from https://www.cato.org/policy-analysis/why-government-should-not-regulate-content-moderation-social-media.

Singapore fake news law a ‘disaster’ for freedom of speech, says rights group. the Guardian.(2019). Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/may/09/singapore-fake-news-law-a-disaster-for-freedom-of-speech-says-rights-group.

The saga of ‘Pizzagate’: The fake story that shows how conspiracy theories spread. BBC News. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-trending-38156985.

Zhang, K., & Kizilcec, R. (2014). (PDF) Anonymity in Social Media: Effects of Content Controversiality and Social Endorsement on Sharing Behavior. ResearchGate. Retrieved 13 October 2021, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283053701_Anonymity_in_Social_Media_Effects_of_Content_Controversiality_and_Social_Endorsement_on_Sharing_Behavior.

The “storm” that digital platforms are going through on content moderation by Teng LIU is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The “storm” that digital platforms are going through on content moderation by Teng LIU is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.