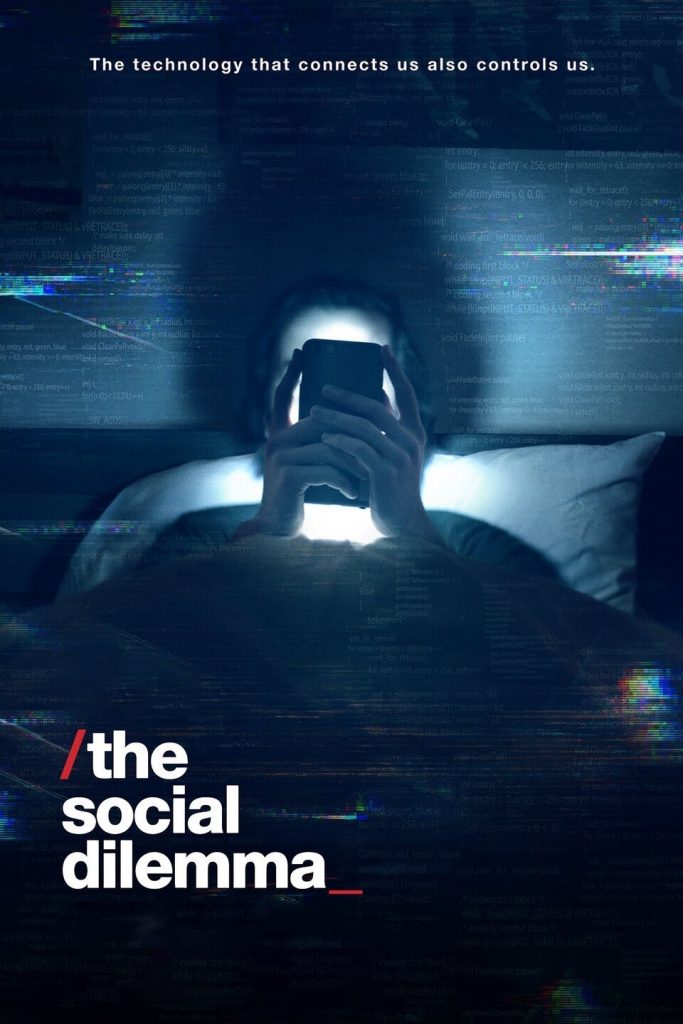

The internet is the gateway to endless possibilities. You have every source of entertainment at your fingertips with billions of links to videos and photos, you have the chance to become famous like pop star Justin Bieber, and you also have the ability to connect on a global scale with loved ones and new people. On a surface level, these platforms are a gateway to happiness for the average person. But on a deeper level, most users are oblivious to the more detrimental impact of smartphones and social networks on human behaviour. The 2020 Netflix film ‘The Social Dilemma’, directed by Jeff Orlowski, is the gateway to the hidden truth of our most heavily consumed and loved platforms. Blended with scripted dramatizations, the film is a collection of interviews with the leaders of Silicon Valley, unanimously confessing to how naive they have been in their work, now fearing the effects of their creations on users’ mental health, the foundations of democracy and the future of our society as we know it.

Building the Silicon Valley Empire

The billion dollar companies that ultimately control the world we live in today, began as small platforms derived to provide a useful service, moving “away from a web of static pages and towards a more dynamic, open and participatory media environment” (Burgess, 2017, p69). Some of the creative executives of the leading companies of Silicon Valley interviewed in ‘The Social Dilemma’, all make it clear that in taking part in the creation and development of Google, Facebook, Instagram, Youtube and all of the dominating platforms of today’s digital landscape, they never intended to become the most powerful companies in history.

“Never before in history have 50 designers, 20- 35 year old white males, made decisions that would have an impact on over 2 billion people” – the film’s leading technology ethicist Tristan Harris

Venture capitalist Roger Mcnamee explains that in the beginning these Silicon Valley companies profited off of products such as hardware and software, but now they’re “in the business of selling their users”. These platforms have the ability to ‘sell certainty’ to other companies wanting to guarantee successful advertising, but the ethical dilemma posed is that these accurate predictions stem from a large amount of data…the data that stems from our addiction.

So how exactly are these companies discretely capitalising on our data? The answer is…your psychology is being used against you.

When the success of the first few Silicon Valley platforms became apparent, competing platforms began appearing. Over time, as the attention economy became more competitive (Brynjolfsson & Oh, 2012), tech companies increasingly added more manipulative artificially intelligent algorithms into their technologies, to try and win the fight for our attention. While individuals are mindlessly scrolling within the digital realm for their own personal consumption, most are unaware of the fact that there are groups of engineers who have designed the platforms in a way that uses your psychology against you. In the designs of these social media sites and search engines, you’re being observed constantly, with the algorithms recording the data of your user patterns, discreetly changing what you see next until they find the patterns that hold the key to influencing your behaviour. Algorithms are making “future-oriented assumptions about valuable and profitable interactions that are “ultimately geared towards commercial and monetary purposes” (Bucher, 2012, p.1169), in order to keep you addicted.

New Notification: “someone liked your photo”

The Social Dilemma uses a dramatization of a typical American family and a personified algorithm, to express how society’s complacency towards surveillance capitalism can lead to the deterioration of each individual user. The teenage son, who the film fixates on, is targeted by a trio of AI figures representing advertising, engagement and growth. This dramatization demonstrates how easily our devices can hold our addiction with endless notifications that reel us back in, even when we step away for just a moment.

Besides sending us notifications to fuel our addictions consciously, we have also been implanted with an unconscious habit to continue scrolling in our never ending news feeds. Former Google Design Consultant Joe Toscano outlines how our constant scrolling and refreshing of platform feeds for new content, is a positive intermittent reinforcement, which Tristan Harris cleverly compares to pulling a lever on a slot machine in Vegas, hoping you might possibly win the jackpot. Our most commonly used platforms hold the ability to “harvest users’ intimate data” (Chambers, 2017, p27), by targeting your trigger points in precise and personal ways that get you to log on. They have the ability to affect real world behaviour and emotions, without having to trigger user awareness.

Likes = Value

According to the contingencies of the self-worth model (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001), self-esteem is shaped by one’s beliefs about what they think they need to be or do to be a person of worth. Due to our increased consumption of digital platforms, our beliefs heavily stem from the perceived sense of perfection that is presented to us online. The rewards we receive, including likes, hearts and comments, are considered a sign of social approval (R. Martinez-Pecino,M. Garcia-Gavilán, 2019), which is what we start to conflate with value and truth, leading us into a vicious cycle in a constant need for approval of others. “Cognitive neuroscientists have shown that rewarding social stimuli (such as likes) activates dopaminergic reward pathways” (Haynes, 2018), so any loss in social approval can lead to mental health deterioration. Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt explains how depression and anxiety immensely accelerated when these platforms first gained traction, leading to a substantial increase in self harm and suicide rates when it comes to girls, which is why the young girl in the family dramatization is an important representation.

The Crumbling of Democracy is where we are headed…

One of the most alarming considerations ‘The Social Dilemma’ experts outline is how algorithmic bias can “enable faster political mobilization” (Couldry, 2015, p1), polarization and opinion fragmentation. It’s one thing to increase our consumption of ads while collecting data that predicts our behaviour, but another to control algorithms to serve us individualized feeds that reinforce our beliefs, helping to foster conspiracy theories and delusional perspectives on the world. Former Google and Facebook engineer Justin Rosenstein explains in the film that if you make a Google search such as “climate change is…”, you are going to see different results depending on who you are and where you live, and not the truth about climate change. ‘The Social Dilemma’ compares our society to the Truman Show, where we each accept the reality we are presented with as the truth, because over time our consumption of these tailored platforms drives us to believe everyone agrees with us. This constant operation on differing information each user is presented with, is when certain individuals are no longer able to reckon with information that contradicts with their online worldview, forming less objective and constructive individuals. Our young teen within the dramatization falls down the rabbit hole of what the film describes as “the extreme centre” (an ironic device of political radicalization), attending a protest because of manipulative online content that reinforces his delusional beliefs. His character represents many who are falling victim to being exploited into believing everything they read online is fact, making our society more divided than ever.

Now that you’re aware everything you do online is out of your control, will you keep scrolling?

Although this film signals our obliviousness towards the surveillance capitalism within our everyday devices, it fails to clearly dictate a light at the end of the tunnel, leaving it up to us to derive a tangible solution for our future with these devices. These platforms have gotten away with this for so long because users were unaware they were being exploited, but does this new knowledge mean that people will start to use technology less or are we already in too deep? It may come down to a matter of individual choice, allowing users to limit their platform usage. It may be up to those in authority to increase legislation and regulations to govern these deceitful platforms and encourage systemic change. (Flew & Martin et al., 2019) It also could be up to the companies and executives like those who came forward in this film, to stand up and help diminish their manipulation of vulnerable everyday humans. One thing for certain is we are in the midst of a dilemma as a society, and it’s important we find a way out of it soon.

References

- Brynjolfsson, E. & Oh, JooHee. (2012). The attention economy: Measuring the value of free digital services on the internet. http://pinguet.free.fr/brynjoo.pdf

- Bucher, T. (2012). Want to be on the top? Algorithmic power and the threat of invisibility on Facebook. New Media & Society, 14(7), 1164–1180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812440159

- Chambers, D.(2016). Networked intimacy: Algorithmic friendship and scalable sociality. European Journal of Communication, Online First, December 16: Sage https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323116682792

- Couldry, N. (2015) The myth of ‘us’: digital networks, political change and the production of collectivity, Information, Communication & Society, 18:6, 608-626, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2014.979216

- Crocker, J.and Wolfe, C. T. (2001). Contingencies of self-worth. Psychological Review., 108, 593–623. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.3.593

- Flew, T, Martin, F., Suzor, N. (2019) Internet regulation as media policy: Rethinking the question of digital communication platform governance. Journal of Digital Media and Policy, 10 (1), pp.33-50. DOI: 10.1386/jdmp.10.1.33_1

- Haynes, T. (2018). Dopamine, Smartphones & You: A battle for your time. Science in the News. Harvard University. https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2018/dopamine-smartphones-battle-time/

- Martinez-Pecino, R. Garcia-Gavilán, M. (2019) Likes and problematic instagram use: The moderating role of self-esteem. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22 (6), pp. 412-416, https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0701

- Rhodes, L.(Producer), & Orlowski, J. (Director). (2020). The Social Dilemma. Netflix. Retrieved from: https://www.netflix.com/watch/81254224?trackId=13752289&tctx=0%2C0%2C72b47cb845166d896406c9b92cf4761e544ed15f%3A984ba02673331afe18c9bf2dfd8a37c086125246%2C72b47cb845166d896406c9b92cf4761e544ed15f%3A984ba02673331afe18c9bf2dfd8a37c086125246%2Cunknown%2C

- Stevenson, M. (2017) From Hypertext to Hype and Back Again: Exploring the Roots of Social Media in Early Web Culture, In Burgess, J. The sage handbook of social media. ProQuest Ebook Central http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/usyd/detail.action?docID=5151795